With the notable exception of the internment of Japanese Americans, World War II still has a reputation as a “good war” for civil liberties. In 2019, for example, the authors of a leading historical work survey text stated that “Franklin Roosevelt had been a government official during World War I. Now presiding over a larger world war, he was determined to avoid many of the patriotic excesses.”

But President Roosevelt’s violations of civil liberties extended far beyond the internment camps. There are few better examples of this than the government’s campaign against the black press. Historian Patrick Washburn, the leading authority on the subject, concluded in A Question of Sedition: The Federal Government’s Investigation of the Black Press During World War II that “the black press was in extreme danger of being suppressed until June 1942.”

The government’s motives were no mystery. The black press had tirelessly documented Jim Crow conditions in the military, federal medical facilities, and defense industries, as well as acts of violence against black troops. These were stories their readers wanted. When William Hastie, dean of the Howard University Law School, shortly after Pearl Harbor asked 56 black leaders to summarize the general attitudes of African Americans, a stunning result 36 said that most did not fully support the war effort.

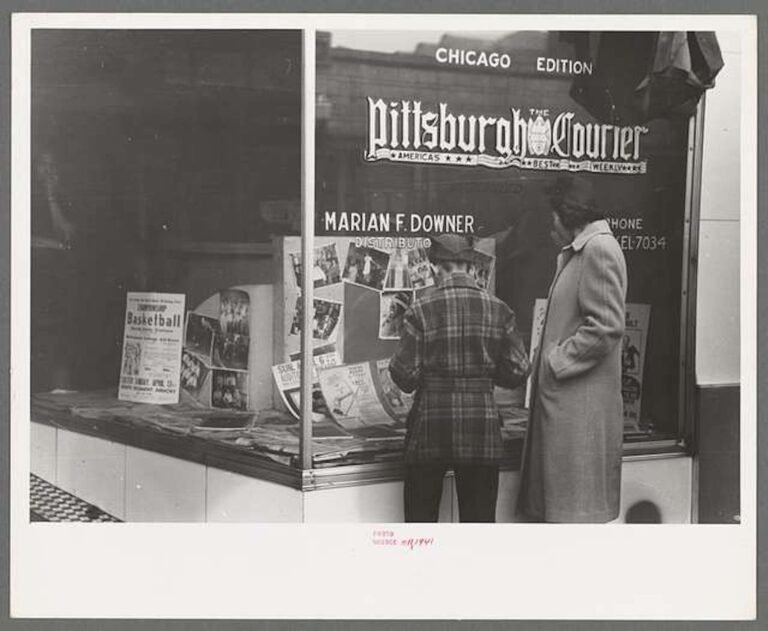

One of the main outlets for this criticism has been the Pittsburgh Courierbest known for making known Double V Campaign (struggle for democracy simultaneously at home and abroad). A strong supporter of this effort was libertarian writer Rose Wilder Lane, who wrote a regular column for the newspaper. THE Mail was no exception in his willingness to question government policy. During this period, New Deal loyalist Archibald MacLeish, who served as both Librarian of Congress and director of the War Department’s Bureau of Facts and Figures, forwarded “seditious” articles from the War Department to Attorney General Francis Biddle. Washington DC, Afro-American and suggested “a very useful preventive effect, if your department could somehow call attention to the fact that the black press enjoys no immunity.” A month later, the president urged Biddle and Postmaster General Frank C. Walker to personally urge black editors to cease “their subversive language.”

Things came to a head in June 1942, when Biddle summoned John H. Sengstacke, the editor of Chicago defender and the president of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), an African-American group, at his office. Placed on the table in front of Sengstacke were copies of several prominent black newspapers, including the DefenderTHE Mailand the African American from Baltimore. Biddle declared them seditious and warned that the government was “I will silence them all” Sengstacke suggested a compromise: newspapers might be willing to tone down their rhetoric if the government agreed not to issue indictments– and agreed to give more access to black journalists.

Biddle gave his verbal agreement, and eventually black editors renounced their desire to challenge wartime abuses. A federal study on the content of Pittsburgh Courier, for example, showed that the newspaper devoted significantly less space to the Double V campaign in April 1943 than in August 1942. Additionally, the primary targets of negative coverage during this period shifted from the federal government to local governments and private companies. A postal inspector noted a notable weakening in the “vigor (sic) of his complaints” for discrimination.

But despite Biddle’s promise, authorities were not more cooperative in sharing information with black journalists. This bureaucratic obstruction led a frustrated Sengstacke to question whether “the government really wants sincere cooperation or whether there are clandestine forces working against the interests of a section of the black press.”

Even though federal authorities did not pursue legal action against the black press during the remainder of the war, that did not mean they took a hands-off approach. Instead, they have intensified both intense surveillance and informal pressure. In the first half of 1942, FBI agents visited major black newspapers that had published articles critical of the federal government. In addition, postal inspectors warned two leading newspapers that the “benefits of citizenship” included an obligation “not to highlight isolated and rare cases in a manner that would hamper recruitment and hamper a another way the war effort”.

Federal officials seemed particularly upset by the articles by George S. Schuyler, editor and columnist at Mail. His arguments that the status quo offered no hope of “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity» and that “the Negrophobic philosophy, originating in the South, had become the official policy of the government”. A Justice Department official responded to the statements by urging the Office of War Information to take “action” against the newspaper.

Schuyler was particularly forceful in challenging the internment of Japanese Americans: “This country probably has as many citizens in concentration camps as Germany. » He rejected accusations that those interned, whom he described as hardworking and thrifty, posed a real threat to national security. Schuyler urged African Americans to look beyond their own grievances, because “if the government can do this to American citizens of Japanese ancestry, then it can do it to American citizens of ANY ancestry… Their fight is our fight.”

Schuyler was exceptional in describing the sufferings of African Americans, Japanese Americans, and right-wing sedition defendants as analogous and interrelated. The Roosevelt administration, he concluded, persecuted them for what they “said and wrote” and had presented no evidence of collusion or participation in a conspiracy. If these individuals could be tried for opposing administration policies, he asked, “then who is safe? I could be arrested for speaking harshly about the brother’s treatment (Secretary of the War Henry L.) Stimson to young blacks in the army.”

Ultimately, informal pressure suited the government’s goals much better than direct legal sanctions. According to an analysis by the Department of Justice underlines, the likely result of legal action against “a newspaper as important and as respected by the Negro population as the Pittsburgh Courier” would be “further unrest and perhaps (arousing) a spirit of defeatism among the Negro population.” It would also almost certainly have alienated many black voters from Roosevelt in key Northern states: Mail had the highest circulation of any black newspaper and had provided past support for Roosevelt. So instead of engaging in politically risky sedition prosecutions against the black press, the government relied on more indirect methods of behind-the-scenes manipulation and intimidation to silence critics.